Letters and Scripture in the Early Church

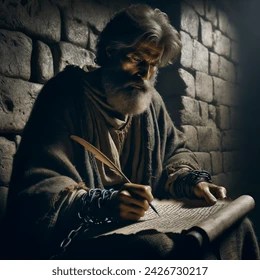

The common notion that early Christians lacked any form of a “Bible” misrepresents New Testament and historical testimony. While bound codices like those today would emerge later, the earliest believers accessed apostolic teaching through letters (epistles) that were both written expressly for, and circulated among, local congregations. These letters quickly formed the backbone of scriptural authority for the new communities of Jesus-followers.

Apostolic Letters: Written, Distributed, and Read Publicly

NT Testimony to Letter Circulation

- Direct Command to Read and Circulate Letters

- Colossians 4:16 (NKJV): “Now when this epistle is read among you, see that it is read also in the church of the Laodiceans, and that you likewise read the epistle from Laodicea.”

Paul explicitly commands the congregation in Colossae to ensure their letter is not only read locally, but also shared regionally and that they reciprocate with letters from fellow believers.

- Colossians 4:16 (NKJV): “Now when this epistle is read among you, see that it is read also in the church of the Laodiceans, and that you likewise read the epistle from Laodicea.”

- 1 Thessalonians 5:27 (NKJV) underscores public reading: “I charge you by the Lord that this epistle be read to all the holy brethren.”

Paul expects all believers in Thessalonica to hear his letter, which again suggests a communal, public engagement. - Public Reading Was Standard Practice

- Revelation 1:3 (NKJV): “Blessed is he who reads and those who hear the words of this prophecy, and keep those things which are written in it…”

The reading aloud of John’s apocalypse follows Jewish synagogue custom, and early church historian Eusebius confirms Paul’s letters were “passed around from church to church, thus ceasing to be regarded as of merely local importance”.

- Revelation 1:3 (NKJV): “Blessed is he who reads and those who hear the words of this prophecy, and keep those things which are written in it…”

- Churches Responding with Questions

- 1 Corinthians 7:1 (NKJV): “Now concerning the things of which you wrote to me: It is good for a man not to touch a woman.”

This reveals that local churches not only received apostolic letters but wrote back to the apostles with questions, showing active correspondence built on written texts.

- 1 Corinthians 7:1 (NKJV): “Now concerning the things of which you wrote to me: It is good for a man not to touch a woman.”

Treasury of Scripture Knowledge: Cross References

- Colossians 4:16 — cross references include 1 Thessalonians 5:27 and 2 Peter 3:15-16 where Peter refers to Paul’s “letters” as authoritative and considered as “Scripture.”

- Revelation 1:3 parallels with Deuteronomy 31:11, which established the Jewish precedent for the public reading of divinely inspired writings.

Early Christian Evidence Outside the NT

- Second-century church authorities (e.g., Ignatius, Polycarp, Clement of Rome) cite, allude to, or request copies of apostolic letters, showing that their circulation was already widespread within decades of the apostles’ lifetimes.

- The earliest collection of Paul’s letters, P46, dates to around the early third century but reflects a copying tradition established much earlier.

- Historical writings such as those from Eusebius, Athanasius, and church councils confirm the general recognition, copying, and reading of the letters, as the “criterion” for their acceptance was based largely on their apostolic origin and broad use in worship gatherings.

The Mechanics of Letter Distribution

- Apostolic letters were delivered “by hand,” often by trusted members named in the texts (e.g., Tychicus in Eph. 6:21, Col. 4:7–8; Phoebe in Rom. 16:1–2).

- The process involved the carrier handing over the letter to church elders (or overseers), who then read the message aloud in the assembly of believers. This oral delivery was crucial in a semi-literate culture and reinforced church unity, doctrine, and connection.

- Letters were not static; copies were made and passed between geographically distant congregations. Paul’s instructions were preserved and multiplied, collectively forming an early New Testament “library” within a few decades.

Dating of the New Testament Letters

While precise dating is debated, most scholars place the NT letters within the first century:

| Letter/Book | Approximate Date Range (CE) | Scholarly Consensus |

|---|---|---|

| 1 Thessalonians | 49–52 | Earliest Pauline letter |

| Galatians | 48–55 | Early to mid 1st century |

| 1 Corinthians | 53–54 | |

| 2 Corinthians | 54–56 | |

| Romans | 56–58 | |

| Ephesians, Philippians, Colossians | 60–62 | Prison Letters |

| Hebrews | Before 70 or 60–90 | Debated, not universally Pauline |

| Gospel of Mark | 65–70 | Earliest gospel |

| Matthew, Luke/Acts | 80–90 | Reflects shared traditions with Mark |

| John | 90–100 | Last Gospel |

| Revelation | 95–100 | High consensus for Domitian persecution |

Most of the NT was written no later than the 90s, with key letters (Paul’s) predating even the destruction of the Temple in 70 AD.

A “Bible” in the Apostolic Age?

While early Christians did not have a bound New Testament as today, they possessed access to a growing collection of authoritative writings – letters from apostles and eyewitnesses which were read aloud, copied, exchanged, and functioned as scriptural guides for faith, doctrine, and living. By the end of the first century, most churches across the Roman Empire had routine access to apostolic writings that would become the New Testament. Their gatherings (ekklesia), often in house churches apart from the later institutional structures, centered on hearing, discussing, and responding to these Spirit-inspired messages in the very way described by the texts themselves.

This practice matches the biblical model of “church” as a participatory body of believers, gathered around apostolic teaching, not subordinate to later institutional traditions. The accessibility and centrality of these letters are affirmed both by Scripture and the earliest post-apostolic historical testimony.

The Importance Placed on These Writings

For the earliest Christians, the letters and gospels circulating among the assemblies were not simply instructional documents or religious tracts; they functioned as the living voice of the apostles through whom Christ was continuing to shepherd His people. The careful public reading, regular copying, and mutual exchange of these texts underscores the high honor and weight placed upon them. As seen in verses like Colossians 4:16 and 1 Thessalonians 5:27, the early church treated these writings as holy and authoritative, foundational for doctrine, correction, encouragement, and sanctification. Their commitment to reading, discussing, and safeguarding these apostolic writings shaped the identity and unity of the church, anchoring them to the teachings of Christ and the apostles rather than to the emerging institutional structures or later traditions. This reverence for the apostolic word, as preserved in Scripture, reflects the conviction that God’s inspired message was to be central in the life and practice of every local assembly.